The Indian Way of Sustainability – Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow!

mata Bhumih putruaham prthivya:

Earth is our mother. We are her children. - Atharva Veda (Prithvi Sukta, shlok no. 12)

The Prithvi Sukta is a Sanskrit chant in the ancient Indian text Atharva Veda, the fourth among the Vedas and believed to be the knowledge storehouse of procedures for everyday life. The shlok (hymn) showcases reverence for Mother Earth, describing it as a living entity and underlining our responsibility to take care of it.

This shlok summarises the essence of India’s age-old ethos of sustainability. The ancient Indian civilisations virtually lived and breathed the sustainability tenet, as seen in their cultural, environmental, behavioural, social, religious and governance philosophies, and as highlighted in this chapter through various examples.

The Indian national song ‘Vande Mataram’ mentions the resourcefulness of the country through the phrase “Sujalam Suphalam, Malayaja Sheetalam”.

(Sujalam - ample potable water, Suphalam - fertile land, Malayaja Sheetalam - hilly, picturesque with fresh and oxygen-rich air quality).

India’s Tryst with Conservation

Among the key facets of India’s sustainability philosophy is its strong focus on saving water. Indian communities have been harvesting rainwater since centuries, using topography-specific techniques.

Water Conservation systems in India date back before 3000 BCE

The King of Bhopal built the largest artificial lake covering an area on 65,000 acres of land in Madhya Pradesh, India in the 11th century.

Engineering features like stone drains and rock-cut wells have been found at Dholavira, a Harappan site from the Indus Valley civilisation that lasted from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, in Rann of Kutch, Gujarat.

The Mudduk Maur Dam near Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh was the highest earthfill embankment dam in the world for three centuries after its construction in the year 1500.

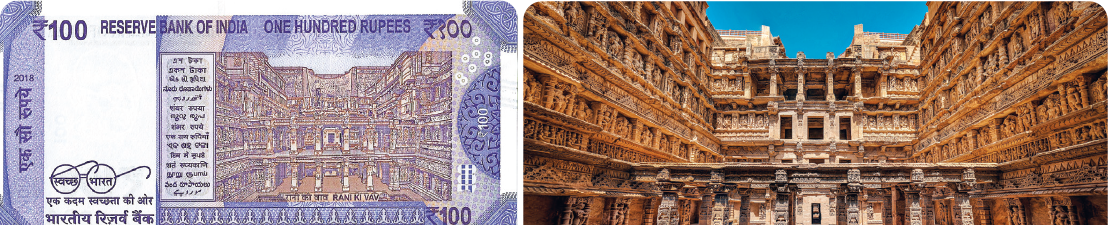

The stepwells further chronicle the story of ancient India’s strong water conservation and harvesting skills. Stepwells are water storage systems that were first constructed in the third millennium BCE (spanning the years 3000 through 2001 BCE) and adopted across various kingdoms in the country. They were designed to make water storage areas resembling ponds or wells accessible by descending flights of steps.

Rani ki Vav (the Queen’s stepwell) is an 11th-century architectural wonder that features on the ₹ 100 currency note, highlighting India's rich and diverse heritage. It is situated in the town of Patan, Gujarat. The stepwell is divided into seven levels of stairs, with a water tank at the fourth level at a depth of 23 metres. It is 65 metres long and 20 metres wide. This subterranean water resource and storage system is designed to look like a temple. It is also a UNESCO world heritage site.

Rani ki Vav is not the only stepwell in India. Agrasen Ki Baoli in Delhi; Adalaj Ni Vav in Gandhinagar, Gujarat; Dada Harir Stepwell in Ahmedabad, Gujarat; Chand Baori near Jaipur, Rajasthan; Meena Ka Kund in Amer, Rajasthan; and Shahi Baoli in Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh are some other prominent stepwells that have survived the test of time.

Remains of ancient stepwells also abound in South India, with a notable example being the Itagi Mahadeva Temple stepwell in Karnataka, which dates back to 1112 CE, when it was built by Mahadeva, a commander in the army of King Vikramaditya VI.

Walking in Yesterday’s Footsteps

These stepwells are not the only example of India’s sustainable living culture. The country’s landscape is dotted with unique tools, methods, systems and processes. It is no coincidence that India's targeted goals which were announced at the Paris Agreement evoked recollections of those ancient times when structures were designed to keep the buildings cool using natural methods without affecting the environment.

The low ceiling of Maharashtra’s Ajanta Caves (left) which was built between 200 BCE and 650 CE and the airy Jharokhas (a type of enclosed balcony) of Jaipur’s Hawa Mahal (right) constructed in 1799 epitomise India’s architectural marvels. The 953 Jharokhas at Hawa Mahal keep the building well-lit and airy at all times.

The use of environment-friendly natural brushes, henna, twigs and rice powder for making the traditional Madhubani painting, dating back to the seventh century CE, endorses ancient India’s sustainability focus. Henna is a reddish-brown natural dye made from powdered leaves of a tropical shrub.

The ancient architecture of designing houses in Kerala, which is making a comeback, comprises a slanting roof that not only allows the rainwater to slide away but also keeps the house cool even in the hot and humid weather that prevails in the state. The internal courtyard ensures enough ventilation and natural light for all the rooms.

A traditional house in Kerala with a slanting roof that allows rainwater to slide away and cools down the interiors.

The Gandhian Way of Living Sustainably

The earth, the air, the land and the water are not an inheritance from our forefathers, but on

loan from our children. So we have to hand over to them at least as it was handed over to us.

With these words, which he had scripted in his 1909 book 'Hind Swaraj' or ‘Indian Home Rule’, Shri Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi effectively defined the principle of sustainability as ‘More from less for more’. This principle is all about enabling greater performance from fewer resources for more people and not just for bigger profits. It seeks to create an equitable society and a sustainable future for mankind.

Gandhi ji’s Equitable Progress Concept

Gandhi ji's philosophy of rural reconstruction was rooted in the principle of Sarvodaya (universal uplift or progress for all). The Sarvodaya movement sought to promote self-sufficiency in rural communities by improved methods of agriculture, promotion of cottage industries and representation of the people through a village council. The philosophy encourages simple living, high thinking and equitable opportunity for everyone to produce and earn sufficiently through work for a dignified living. This concept finds resonance in the Indian government’s recent Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-reliant India) campaign, which encapsulates the vision of a new India with the aim to make the country and its citizens self-reliant in all senses.

A statue of Gandhi ji

Gandhi ji's Zero-waste Lifestyle Approach

He walked or cycled instead of using fuel-powered transportation (walking an average of 18 kms a day).

He only used the minimum required water for taking his daily bath from the water of the Sabarmati river flowing near his Ashram. He also built his ashrams on wastelands.

He and his followers used scraps of papers for writing notes and reusable envelopes to send letters.

Fostering Sustainable Development - From Then to Now!

India's legacy of sustainability lives on as an all-pervasive and deep-rooted national ethos. Its sustainability focus continues to find resonance in its modern growth agenda. India has committed itself to stiff climate change and environmental sustainability targets, despite being ranked extremely low in global per capita emissions.

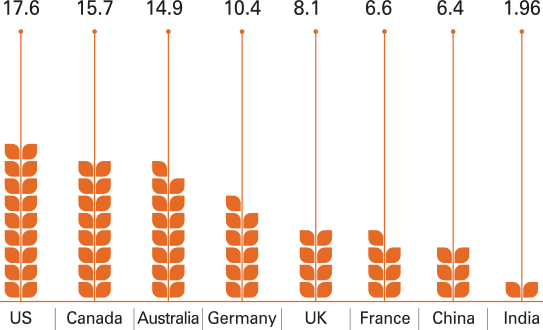

Per capita GHG emissions

India’s per capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emission stands at 1.96 tCO2e (tonne carbon dioxide equivalent), as per the data presented in the G20 meeting held in July 2021. This is less than one-third of the world’s per capita GHG emissions of 6.55 tCO2e.

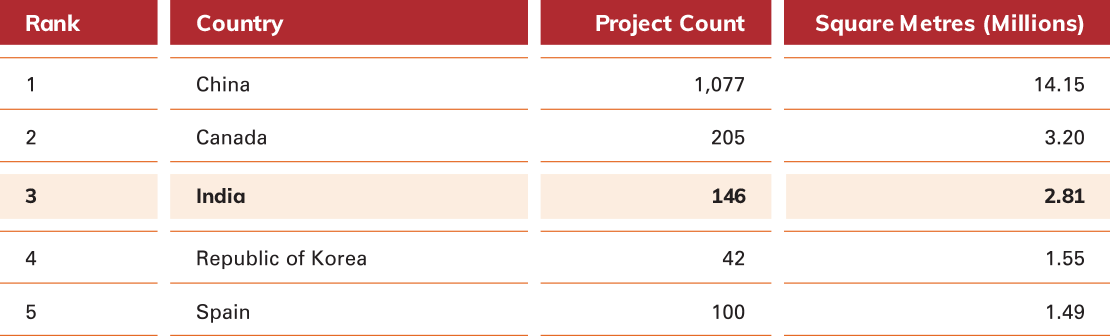

India ranks third in LEED list

India ranked third in the world in the 2021 list of top 10 countries outside the US for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), released by the US Green Building Council (USGBC). India has been awarded for making significant strides in healthy, sustainable, and resilient building design, construction, and operations.

Source 2: https://www.usgbc.org/articles/usgbc-announces-top-10-countries-and-regions-leed-2021